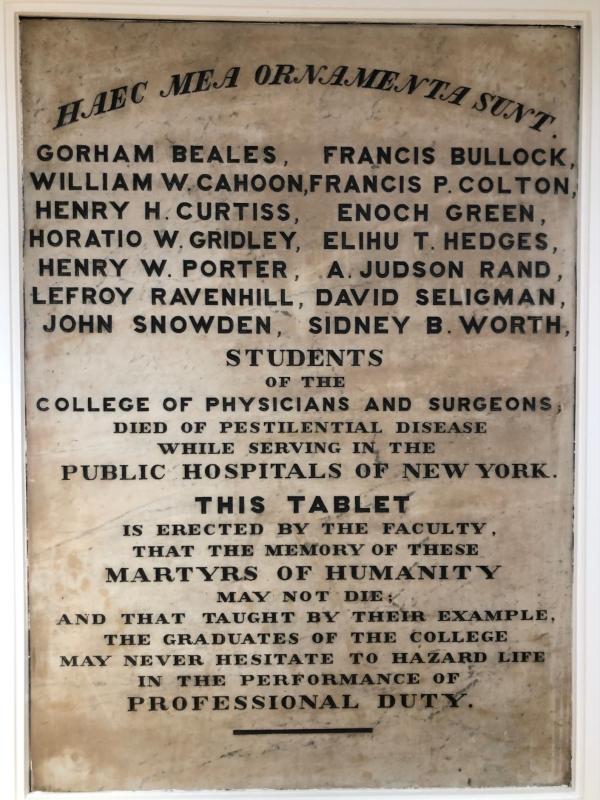

Out of sight in a room inaccessible to most Medical Center staff is a more than 160 year old marble tablet commemorating 14 heroic VP&S students who died while serving their patients. It’s also a rare survivor of a long-gone medical school building.

Erected in 1856, the tablet is a memorial to those medical students who, it says, “died of pestilential disease while serving in the public hospitals of New York.” Originally placed it what was then the brand-new medical college building at the corner of East 23rd Street and Fourth Avenue (now Park Avenue South), the tablet followed the medical school to its subsequent homes on West 59th Street and in the Washington Heights neighborhood. Though the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons is more than 250 years old, nothing survives of its previous seven homes. All have long been demolished as New York City constantly renews itself.

Besides being a poignant reminder of the hazards of the physician’s life, the tablet is the only surviving structural object from the previous VP&S buildings – as distinct from such portable items as portraits, books, or archival records. Located in room 1-141, a lounge for medical students on the first floor of the VP&S building, the tablet is only accessible to those with a medical student ID card – making it out-of-sight for everyone else.

It’s not known why the medical faculty decided to create the memorial when it did, nor do we know who paid for it or crafted it. Its only mention in the faculty minutes is an October 15, 1856 motion recording that “it was Voted that the Monumental Tablet be placed in the lower Lecture Room of the College." [1] A thorough search of the medical school’s surviving financial records doesn’t reveal who created it, though it’s probable it was fashioned by a funerary monument shop.

A New York Times article on the opening of the college’s new academic year on October 20, 1856 [2] mentions it, while the opening address delivered that day by Chandler R. Gilman, professor of obstetrics, diseases of children, and medical jurisprudence, devotes a paragraph to it.

Gilman’s address, later published as The Relations of the Medical to the Legal Profession (New York: Baker & Godwin, 1856), begins with a mention of the college’s new building opened that January on East 23rd Street. He then pauses to “devote a single moment to one of its ornaments”:

On this tablet are engraven the brief histories of some who have gone before you, and who, after short service, have been enrolled among those whose names Science and Humanity will never allow to die…When pestilence was rife in our hospitals,--when in those wards devoted to public health, Death held high festival, selecting his daily victims at his will,--when to minister to the afflicted and dying , was almost certainly to share their fate, these graduates of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, were ready to labor night and day in the cause of suffering humanity…[3]

Under the heading of a Latin motto “Haec mea ornamenta sunt” (These are my ornaments), the tablet lists the names of 14 "martyrs of humanity." However, contradicting Gilman’s assertion, these are not all VP&S graduates. Two received their medical degrees from New York University; one received his from Yale; and for another his degree is unknown though it’s clearly not from P&S. Two more appear to have been still students at P&S at the time of their death.

Research discovers what the “pestilential disease” was that killed them. Though this author was told when he first saw the tablet in 1997 that the students memorialized had died of cholera, a search through newspapers and medical journals of the era shows that every one of them fell victim to typhus -- in two cases called “ship fever” but almost certainly the same thing.

Although the 19th century often confused the terms “typhus” and “typhoid fever,” in this case typhus was almost certainly the culprit. A louse-borne disease typically found in crowded conditions among under-nourished populations (think of the “de-lousing stations” of World War I), typhus would have been particularly prevalent in New York’s public hospitals during the period (1847-1853) in which these men died. This correlates almost perfectly with the horrific Irish Potato Famine of 1845-1851 which killed about one million Irish and sent another million overseas, primarily to the United States.[4]

Crowded into sub-standard “coffin ships” these immigrants arrived sick, malnourished, and often already ill with typhus. Not surprisingly, most of the VP&S graduates commemorated on the tablet were working at exactly the places where these ill Irish immigrants would have been hospitalized upon landing in New York: Bellevue, the Emigrant Hospital on Ward’s Island, or the Quarantine Station on Staten Island.[5] These were dangerous places to work but also an excellent method of gaining medical experience at a time when U.S. medical schools offered scant clinical training. As might be expected the victims were young: of the ten whose age at death can be uncovered all were between 24 and 34 years old.

More than a century and half later, the tablet remains to both inspire and caution another generation of medical students. As recent years have shown, the threat of “pestilential disease” has not yet been vanquished.

Further research on the persons named on the tablet has been done by Archives & Special Collections staff and is available by contacting hslarchives@columbia.edu

[1] College of Physicians & Surgeons, Faculty Minutes, Oct. 15, 1856, vol. II, page 7.

[2] New York Daily Times, Oct. 21, 1856, page 4

[3] Gilman, Chandler, The Relations of the Medical to the Legal Profession (New York: Baker & Godwin, p. 5-6)

[4] The literature on the Irish Potato Famine is vast. A good place to start is the Wikipedia article (accessed Nov. 2, 2022): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Famine_(Ireland)

[5] Of the 14 names on the tablet, 10 died at Bellevue, Emigrants’ Hospital, or the Quarantine Station. Of the rest, 1 died at New York Hospital, one at Kings County Hospital, one at the Kings County Lunatic Asylum, and another at the Seamen’s Retreat on Staten Island.